On complex projects—tall buildings in Vancouver, essential facilities in higher seismic zones, or structures with unusual geometry—the prescriptive NBCC pathway can start to feel limiting. Performance-Based Design, or PBD, is the framework that lets us define how the building should behave and then design backwards from those objectives.

Instead of only asking “Did I follow all the rules?”, PBD pushes us to ask “Will this building do what we need it to do when the shaking starts?”

For us Canadian engineers, with the diverse challenges our geography and climate present, understanding PBD is about building smarter, more resilient structures. This article introduces the basics: what PBD is, why it matters (especially here in Canada), and some of the key terminology you’ll need.

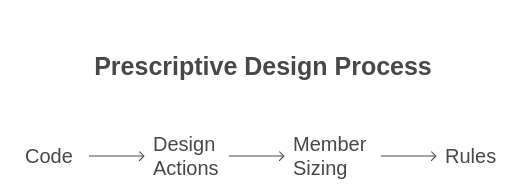

Prescriptive vs. Performance: What’s the Big Deal?

So, what’s the fundamental difference?

Think of Traditional Prescriptive Design – the bread and butter of much of our daily work following codes like the National Building Code of Canada (NBCC). It’s like following a detailed recipe. The NBCC and our material standards (CSA S16 for steel, CSA A23.3 for concrete, etc.) tell us the specific ingredients (minimum member sizes, material strengths, detailing requirements) and the methods to combine them. If you follow the recipe meticulously, you expect a certain outcome – generally, a safe structure. The focus is on the means. For example, the code might say, “For this type of building in this seismic zone, your columns must be at least X size with Y reinforcement.”

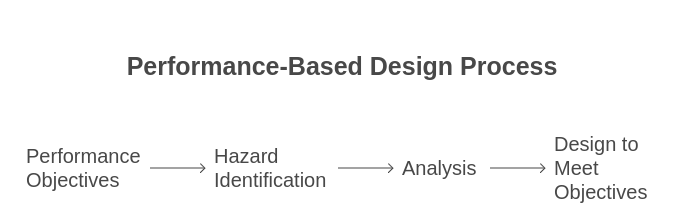

Performance-Based Design (PBD), on the other hand, is like defining the desired qualities of the final dish before you even pick up a whisk. You might say, “I want a three-layer cake that’s moist, can support elaborate decorations, and won’t crumble if the table gets bumped.” As the engineer (or chef, in this analogy!), you then select the best ingredients, techniques, and analyses to achieve that specific outcome. The focus is squarely on the end performance.

Key Takeaway: PBD asks, “How should this building behave under specific conditions?” rather than just, “What are the minimum prescriptive rules I need to follow?”

For a building, a PBD objective might sound like: “After a design-level earthquake, the building should be safe for occupants to exit, and critical structural elements should be repairable within three months, allowing for re-occupancy.” This is a much more explicit performance goal than just satisfying code-mandated force levels.

Why Bother with PBD? The Upsides for Your Projects

You might be thinking, “The NBCC already aims for safety. Why add another layer of complexity?” Fair question. But PBD offers some compelling advantages:

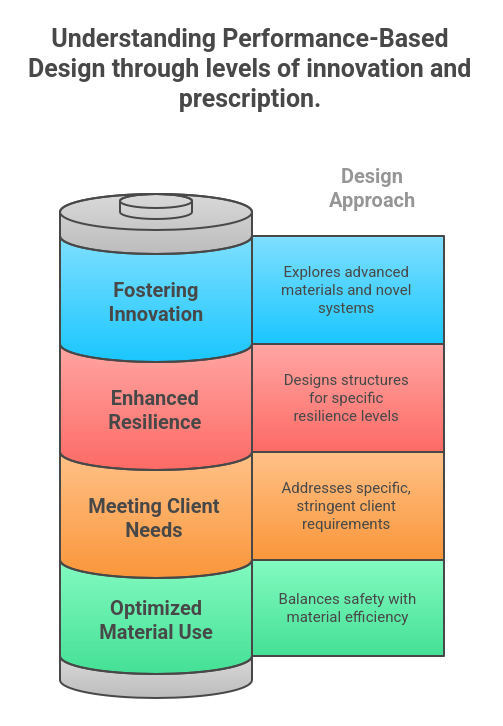

- Enhanced Resilience: This is a big one. PBD allows us to design structures to specific levels of resilience beyond just preventing collapse. Think about a hospital in Vancouver needing to remain operational after a significant seismic event, or a critical data centre that can’t afford downtime. PBD provides the framework to achieve these higher performance targets.

- Meeting Specific Owner/Client Needs: Let’s face it, a one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t always cut it. An owner of a high-tech manufacturing facility will have very different performance expectations regarding vibrations and operational continuity compared to the owner of a bulk storage warehouse. PBD allows us to tailor the design to these unique, often more stringent, client requirements.

- Potential for Optimized Material Use (and Economy): By getting a much clearer understanding of how the structure will actually perform under various loads, especially in the inelastic range, we can often use materials more efficiently. This doesn’t always mean cheaper upfront (especially if the performance targets are very high), but it can lead to significant lifecycle cost savings by minimizing damage, reducing repair costs, and limiting business interruption.

- Fostering Innovation: Prescriptive codes, by their nature, can sometimes limit innovation because they prescribe specific solutions. PBD, by focusing on the “what” (performance) rather than the “how” (specific rules), opens the door for engineers to explore advanced materials, novel structural systems (like base isolation or an advanced facade system), and cutting-edge analytical techniques to achieve the desired outcomes.

Getting a Handle on the Terminology

Before we dive deeper in future posts, let’s get some common PBD terms straight. You’ll hear these a lot:

- Performance Objectives: These are the cornerstone. They are clear, explicit statements that link a specific Hazard Level to a desired Performance Level. For example: “For a seismic event with a 2% probability of exceedance in 50 years, the structure shall achieve a Life Safety Performance Level.”

- Hazard Levels: This defines the intensity of the event we’re designing for (e.g., an earthquake with a certain return period or probability of exceedance, like the NBCC’s 2%/50 year design earthquake, or perhaps a more frequent, lower-intensity event for serviceability checks).

- Performance Levels: These are qualitative descriptions of the building’s expected state after experiencing a specific hazard level. Common ones, especially in seismic PBD, include:

- Operational (OP): Basically, business as usual. Minimal damage, building is fully functional.

- Immediate Occupancy (IO): Safe to re-enter and use. Minor, repairable damage.

- Life Safety (LS): Significant damage, but the structure has prevented widespread collapse, allowing occupants to exit safely. This is often the baseline for standard code design.

- Collapse Prevention (CP): The building is on the verge of collapse but hasn’t, protecting lives. Likely irreparable.

- Acceptance Criteria: These are the specific, quantifiable limits used to determine if a Performance Level has been met. Think interstory drift limits, material strain limits, plastic hinge rotation limits, or allowable damage to specific components. These are the numbers our analysis results get compared against.

Why This Matters for Us in Canada

For those of us practicing in Canada, particularly in seismically active zones like British Columbia (shout-out from Coquitlam!) or parts of Quebec and the Yukon, PBD is becoming increasingly relevant. While the NBCC provides a solid framework for seismic safety, PBD offers the tools to:

- Design structures that go beyond the minimum life safety requirements, aiming for enhanced post-event functionality and reduced recovery times – crucial for community resilience.

- Tackle complex projects like tall buildings, structures with unusual geometries, or critical infrastructure where prescriptive rules might be less applicable or overly conservative. Vancouver has certainly seen its share of PBD applications for innovative structures.

- Explicitly address owner demands for higher performance, which is becoming more common as awareness of seismic risk and business continuity grows.

The NBCC itself is evolving. As we’ll discuss later in this series, recent versions (like NBCC 2020) are introducing more explicit performance requirements for certain building types, pushing us further into performance-based thinking.

What’s Next?

Hopefully, this gives you a good initial taste of what Performance-Based Design is all about. It’s a powerful approach that puts us, the engineers, more in control of achieving specific outcomes for our structures.

For a deeper look at assembling the team and setting performance goals, see Assembling Your Team & Nailing Down Performance Goals for a typical PBD process and the key players who need to be at the table.