After setting up your structural model, defining your sections, and then the software pops up a field asking for “shear area.” What do you put there? If you’re like many engineers, you’ve probably typed in zero and moved on. But do you actually know what that does to your analysis?

This post breaks down the often-overlooked shear area input and explains when it can significantly affect your results.

What Does That Shear Area Field Actually Do?

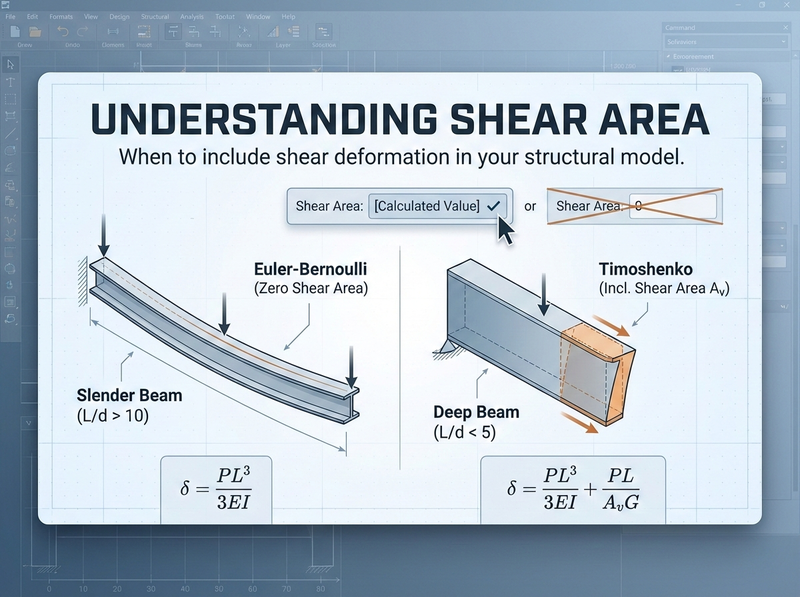

When you enter a value for shear area in your structural software, you’re telling the program whether to include shear deformation in the stiffness calculations. Here’s the key thing many engineers don’t realize:

Entering zero doesn’t mean “zero shear capacity.” It means “ignore shear deformation entirely.”

Most commercial programs interpret a zero value as an instruction to use classical Euler-Bernoulli beam theory, which assumes plane sections remain plane and perpendicular to the neutral axis. This works great for slender beams where bending deformation dominates. But for deeper sections or shorter spans, shear deformation can add meaningfully to your total deflection.

A zero in the shear area field doesn’t break your model—it just tells the software to skip the shear flexibility contribution. For most typical beams, that’s perfectly acceptable.

Why Shear Area Isn’t Just “Area”

Here’s where it gets interesting. The shear area you need to enter isn’t the same as your cross-sectional area. Shear stress doesn’t distribute uniformly across a section—it varies parabolically for rectangular sections, with maximum stress at the neutral axis and zero at the extreme fibres.

The “shear area” (often written as \(A_v\) or \(A_s\)) is an effective area that accounts for this non-uniform distribution. For common shapes:

Rectangular sections:

$$A_v = \frac{5}{6} \times b \times d = \frac{bd}{1.2}$$That 5/6 factor (or dividing by 1.2) comes from integrating the actual shear stress distribution and finding the equivalent uniform stress that gives the same strain energy.

I-shaped sections:

$$A_v \approx A_{web} = d \times t_w$$For wide-flange sections, the web carries almost all the shear, so using the web area is a reasonable approximation. Some references use more refined factors, but the web area gets you in the right ballpark.

Other sections: The shear area factor varies by geometry. For solid circular sections, it’s about \(A/1.11\). For thin-walled tubes, the calculation gets more complex. Check your steel design manual or structural analysis textbook for the specific form factor for your section type.

If you’re using standard steel sections from a library, the software often has the shear area already calculated. Double-check your section properties to see if \(A_v\) is populated—you might not need to enter anything manually.

When Does Shear Deformation Actually Matter?

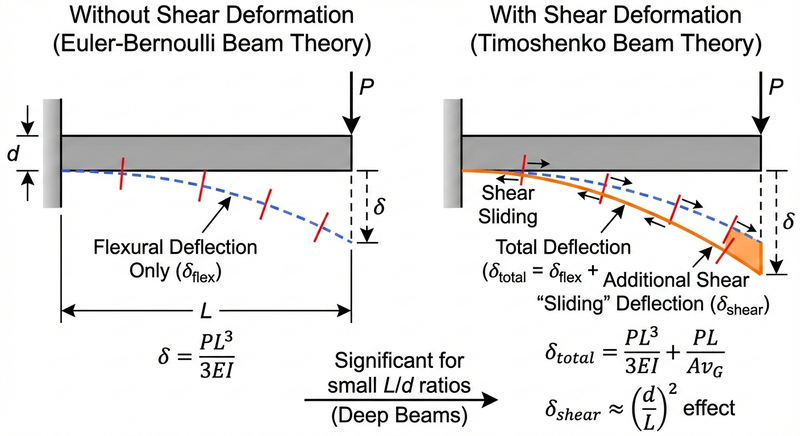

The total deflection of a beam has two components:

- Flexural deflection (from bending): Proportional to \(PL^3/EI\)

- Shear deflection (from sliding): Proportional to \(PL/(A_v G)\)

For a tip-loaded cantilever, the deflection formula including both effects is:

$$\delta_{total} = \frac{PL^3}{3EI} + \frac{PL}{A_v G}$$The ratio of shear deflection to bending deflection scales roughly with \((\frac{d}{L})^2\). This means:

- Span-to-depth ratio > 10: Shear deformation is typically less than a few percent of total deflection. You can safely ignore it.

- Span-to-depth ratio between 5 and 10: Shear effects start becoming noticeable—maybe 5-15% of total deflection.

- Span-to-depth ratio < 5: You’re in “deep beam” territory. Shear deformation can be 20-30% or more of your total deflection. Ignoring it will underestimate your deflections.

Common Mistake: Modeling plate girders, spandrel beams, or transfer beams as standard beam elements without including shear area. These members often have low span-to-depth ratios where shear flexibility matters.

The Stiffness Matrix Connection

For those who want to understand what’s happening mathematically, the beam stiffness matrix changes when you include shear deformation. The modified stiffness matrix includes a factor Γ:

$$\Gamma = \frac{12EI}{A_v G L^2}$$When \(\Gamma = 0\) (infinite shear area), you get the standard Euler-Bernoulli stiffness matrix. As \(\Gamma\) increases, the beam becomes more flexible. The stiffness terms get multiplied by \(1/(1+\Gamma)\), which is always less than 1.

What this means practically: including shear deformation makes your structure more flexible, leading to larger deflections and potentially different load distributions in indeterminate structures.

Practical Guidance

Here’s a quick decision framework:

You can probably ignore shear area (enter zero) when:

- Standard floor beams and joists (\(L/d > 12\) typically)

- Roof beams and purlins

- Most moment frame members

- Any situation where deflections aren’t critical and you’re comfortable with slightly conservative stiffness

You should include shear area when:

- Plate girders and deep transfer beams

- Stub cantilevers (corbels, short bracket arms)

- Spandrel beams with low \(L/d\) ratios

- Any member where you need accurate deflection predictions

- Modeling deep beam-column joints with rigid links

- Seismic analysis where accurate stiffness distribution matters

When you’re learning the software, try running the same model with and without shear area for a simple cantilever. Compare the deflections. This hands-on check will give you intuition for when the effect is significant.

Software-Specific Notes

Most commercial programs handle this similarly:

- SAP2000 / ETABS: Zero shear area means shear deformation is excluded. Section properties from the built-in database often include \(A_v\) values.

- S-Frame: Incorporates shear deformation modification when shear area is specified. Check their documentation for the exact formulation.

- RISA: Similar behaviour—zero excludes shear effects.

If you’re using a program that doesn’t explicitly ask for shear area, check whether it’s using Timoshenko beam theory (includes shear) or Euler-Bernoulli (excludes shear) by default.

A Quick Validation Approach

Not sure if shear deformation matters for your specific situation? Here’s a simple check:

- Calculate the flexural deflection using hand calculations: \(\delta_{flex} = PL^3/(3EI)\) for a cantilever, or the appropriate formula for your configuration

- Estimate the shear deflection: \(\delta_{shear} = PL/(A_v G)\)

- If \(\delta_{shear} / \delta_{flex} < 5\%\), you’re fine ignoring shear effects

- If it’s approaching 10-15% or more, include the shear area in your model

For rectangular sections with typical steel properties (\(E/G \approx 2.6\)), this ratio works out to roughly:

$$\frac{\delta_{shear}}{\delta_{flex}} \approx 2.6 \times \left(\frac{d}{L}\right)^2$$Plug in your depth and span to get a quick sense of whether it matters.

Comparison of deflected shapes for a cantilever beam with and without shear deformation, showing the additional “sliding” displacement from shear

Connecting Back to Your Model

So what should you actually do when that shear area field pops up?

For most routine work: Enter zero and move on. You’re in good company—this is standard practice for typical beam elements where \(L/d\) is large.

For deep members: Calculate \(A_v\) using the appropriate form factor for your section shape. For rectangles, that’s \((5/6)bd\). For I-shapes, use the web area as a starting point.

When accuracy matters: Include shear area, especially for deflection-sensitive applications or when validating against test results or more detailed FEA.

The key is knowing what your software does with that input and making a conscious decision rather than accepting defaults without understanding them.